Antithesis

Amid the chaos of the city that she was calling her home for a little while now, there were only two sights calm and peaceful: the surface of the river and the setting of the sun. On the bridge, people were gathering to welcome the evening coolness closing in. She walked by them over the golden water while pondering the last minutes of the day away.

The Nile, lifeline of the country. In ancient Egypt, the river had been represented by Osiris, the first pharaoh and the god of the afterlife and fertility. He had repeatedly died and come back to life: his death symbolized the yearly drought and his rebirth the periodic flooding of the Nile. The land, fecundated during the floods, was personified by his sister and wife Isis, the goddess of the earth. She was the one who had brought Osiris back to life, and was seen as the dominant partner.

Some contend that this mythology reveals a former mindset: from a period in which women were more powerful than men. This is disputed; in the ancient world, women were generally kept subservient and Egypt knew very few female rulers. True is however that the very first gods were goddesses. They developed some thousands of years ago, in the Neolithic period: voluptuous women who symbolized fertility, the foundation of existence.

She glanced towards the horizon as she walked over the water. The Nile was now bordered by massive concrete and didn’t flood anymore to fertilize the soil. The bridge had become the stage of a whole different way of worshiping fertility.

She hadn’t learned much of the regional dialect yet, but she was perfectly aware of the nature of the sounds fired at her in the streets of North-Africa. Time and again it bewildered, surprised, flattered and annoyed her: the never-ending stream of stares and comments. Stepping out of her front door was the kick off of a series of confrontations with the other sex until she set foot in a safe haven again.

A German anthropologist of the nineteenth century, Johann Jakob Bachofen, had in analogy to the story of Isis and Osiris conceptualized the whole history of mankind as a battle of the sexes: between the feminine principle – material, corporeal, earthly, instinctual – and the masculine principle – immaterial, non-corporeal, spiritual, rational. Since antiquity the woman had been identified with the body, the man with the mind.

On that bridge over the Nile she could relate very well to the dichotomy. It was exactly how she experienced her femininity here: she felt first and foremost a physicality. Observed everywhere, she was constantly very aware of her physical existence – as a woman, and as a foreigner: the distinctness of her appearance guaranteed even more stares. And she represented the material in yet another way: an atheist, attached to worldly reality instead of the spiritual – in a society where religion was present in all aspects of life.

Religion interrupted her thoughts at the top of its voice. The first muezzin soon received echoes from different directions and within seconds the canon turned into a cacophony of calls to prayer, all praising the spiritual, the masculine – their God.

She let the sounds fill up her mind for a while as she continued walking. She left the bridge behind her and headed into the direction of the city center, where there were more mosques than trees and where it often happened that a loudspeaker revealed the location of yet another mosque she had never noticed before.

In downtown she had to slalom her way through the crowds. The area was full – the city was. Everyone had their place in it, and all were carefully watching how others were occupying theirs. The air was grey, the sky was small.

It had been after the rise of the first cities that the goddesses of fertility turned into gods. Division of labor had emerged and no longer was everyone a farmer for whom the harvest was the sole crucial factor for survival. And so the divine was reshaped in the image of those who called the shots on earth: men. Humans had become to see themselves as distinct from nature – like here in the city – and superior to it instead of part of it: they were spiritual beings, not just physical. Opposed to nature – to Mother Earth, to the feminine.

She had no idea how to discern the spiritual under the tangible, stifling pressure the city exerted on her. Her musings made her not any less aware of the attention she received. Her eyes never asked, but were responded all the time. She looked straight ahead and pretended to ignore all attempts to interaction.

A comment, a gesture. It was probably his unusual modest approach that made her follow his look, down to her hip. A small stroke of skin was visible. She gave the young man a suggestion of a smile while she quickly but meticulously made sure to cover up everything that could possibly make any alarm bells go off; everything that reminded that she was a naked body underneath.

The look she had given the man had been thankful rather than disturbed: he had helped her not to disturb any others and he had maybe even thought it better for her own well-being. In this society, women’s physicality was something to be carefully neutralized. Her look had reflected how she didn’t feel being oppressed in the sense many like to think, but at the same time how women were left no real choice because the alternative would influence one’s safety or place in a community. Truth was that, in the excruciating summer heat of Cairo, she felt increasingly frustrated about the clothes sticking to all of her skin. I have to torture myself because men cannot control their hormones, she found herself repeatedly thinking; a futile protest, but not really intended as one anyway.

The fundamental assumption bothered her the most: men were portrayed as slaves to their instincts and desires. Tight clothing on a woman was then seen as so intensely seductive or obviously inviting that hormones take over and bypass reason – leaving women no reasonable alternative to conformism. To protect herself, a woman has to protect men against themselves. She has to make herself resistible. The woman was to be the responsible one, prudent, rational – wasn’t that supposed to be the masculine principle?

She saw more and more clearly that this whole age-old dichotomy, fabricated by western, male minds, was corrupted. Had women not first come to symbolize subjugation to carnal inclinations and were they now expected to oppress that, while men didn’t have to? Had men not ascribed to themselves rationality and then somehow also the inability to control irrational behavior? Was harassing women in the streets not the exact opposite of men’s own carefully crafted image of themselves? That is to say, if men wanted to show their masculinity by harassing women, were they actually, in their own discourse, displaying their feminine side? Were women in that sense becoming the victims of men’s unrestrained femininity? And were men unable to control the symptoms because they had only ever recognized and problematized them when pertaining to the other sex?

It dazzled her. She was unsure whether the dichotomy actually made very little sense, or whether it hinted at an answer to why the relationship between the sexes was so tense here: disconnected, yet both sides profoundly characterized by the antagonism; platonic, yet every encounter a bold intrusion – indeed too often becoming physical as well.

Her failure to understand this foreign world aroused a disheartening hesitancy as she reflected on her theorizing about the mindset of her objects of study. She suddenly felt appalled by her own blatant generalizations based on what she saw in the streets, and was hit by a vague mix of pity and shame towards her lovely North-African friends. As an outsider, would she ever be able, and accepted, to make sense out of it all?

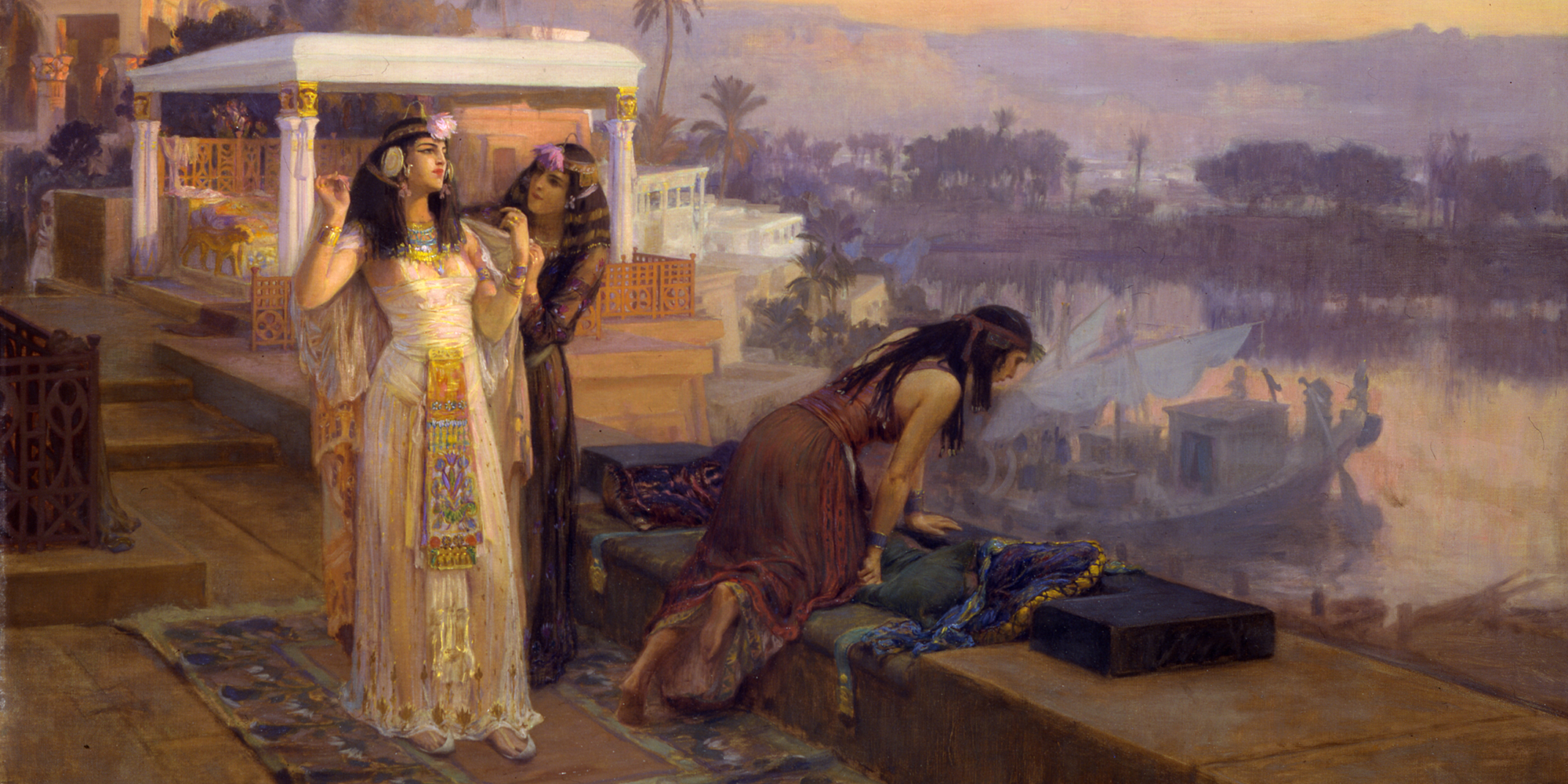

Once again she reflected on this crooked dualism. According to Bachofen, the antagonism extended to all of life: culture versus nature, light versus dark, sun versus earth, right versus left, west versus east. Occident and Orient: the former represented the male, the latter the female; epitomized by the war between the Roman patriarchy and Cleopatra. In colonial times, the added elements of the oppressor – superior – and the oppressed – inferior – became prevalent.

It was the way people were treating her. She admired the Arab hospitality, but she was well aware of the element of her foreignness. She was special, in an all too positive way: people were interested in her, were carrying her around like a trophy, privileging and glorifying the foreign and, as a consequence, passively discriminating against themselves. Sometimes the attention was almost suffocating, as much as the heat and pollution and social norms.

She was received in as well as confronted with this culture as a European first, as an individual second. And she realized that it was fuelled every time she identified or highlighted a difference between her and the others, indeed every time she was surprised about something. It was inevitable and the danger was lurking everywhere: consciously or unconsciously providing differences with labels of inferiority and superiority.

She had arrived, but paused before she left the streets. For a few seconds she looked over her shoulder, in one of those rare moments of awareness when time seems to bypass oneself and place is all-encompassing.

There she was: a woman in a male-dominated society; an atheist among theists; a European in the Orient.

She suddenly felt exhausted and opened the door, eager to leave her reflections and worries on the doorstep.

As she went inside, she realized that the biggest antithesis was that she felt so much at home.

I was inspired by this video to use my habitual walk over the Qasr Al-Nil bridge as a departure for my story. The video, which quite accurately reflects my own experiences of living in Cairo (read an earlier post here), was made by two filmmakers who are working on a documentary ‘The People’s Girls’ about sexual harassment in Cairo. Click here to visit their Facebook page.

For those women in Egypt who can relate to these experiences – everyone! – please visit harassmap.org.

The painting at the top of this post is ‘Cleopatra on the Terraces of Philae’ by Frederick Arthur Bridgman (1896).